Into the Wilderness - George Washington and the War That Forged a Leader (1752–1758)

This is the story of how a 20-year-old Virginian aristocrat walked into the fire of the French and Indian War… and came out a hardened leader.

The Soldier Emerges: A Colonel at 20

In 1752, tragedy struck again. Washington’s half-brother Lawrence Washington, his mentor and closest male role model, died of tuberculosis. Shortly after, George inherited his colonel’s commission in the Virginia militia—a decision more political than practical, but one that changed his destiny.

Without formal military education, Washington relied on self-discipline, observation, and pure determination.

Virginia’s Frontier: A Brewing Storm

By 1753, tension was boiling between the British colonies and French forces pushing in from Canada. Native American tribes were caught between both powers. Virginia’s governor needed someone brave—and expendable—to deliver a warning to the French: leave or face war.

Washington, now just 21, was chosen.

Washington’s winter expedition to Fort Le Boeuf was grueling. He survived freezing temperatures, Indian ambushes, and near-drowning—all before delivering the message and returning.

The French ignored it. War was coming.

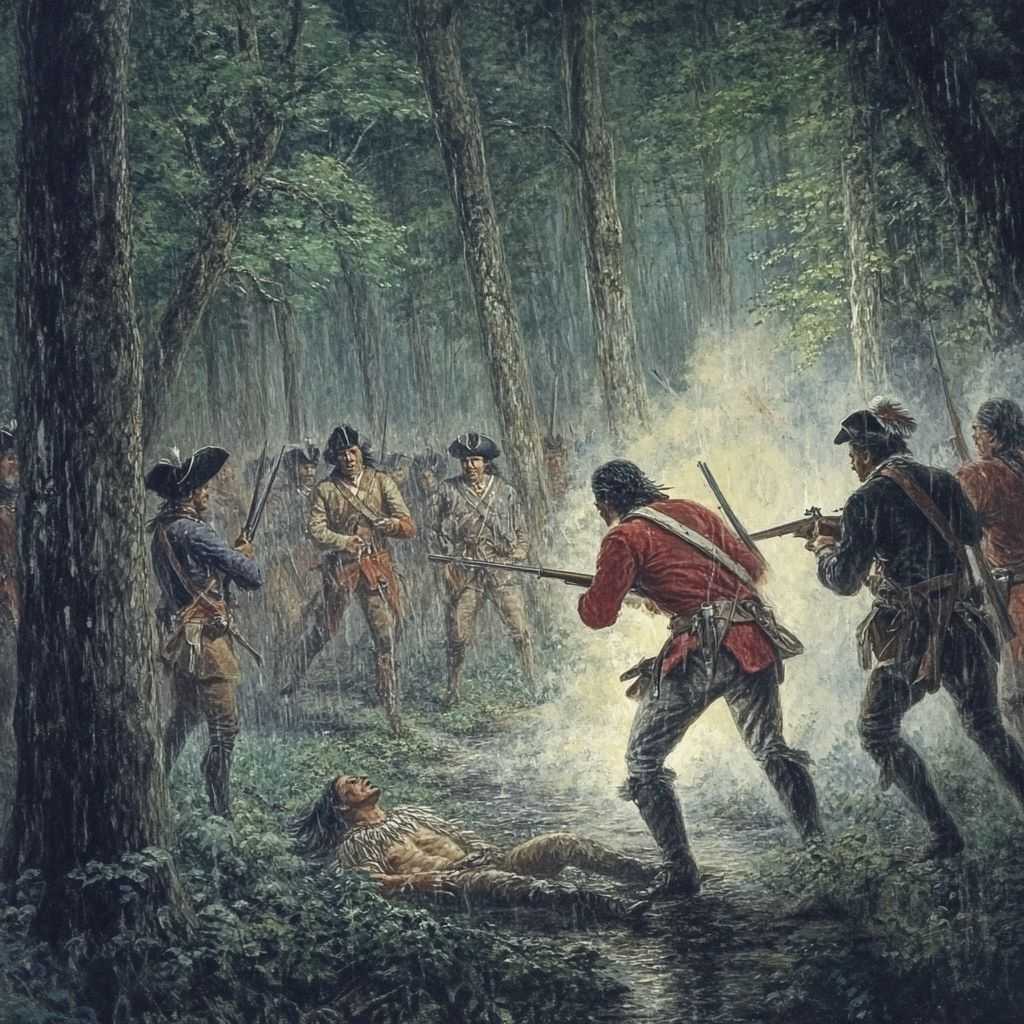

Jumonville Glen: The Shot That Lit a War

In May 1754, Washington led a preemptive strike against a small French party near what is now Pennsylvania. With the help of Native allies, including the fierce Tanacharison (the Half-King), Washington ambushed and killed the French commander Joseph Coulon de Jumonville.

What Washington didn’t realize was that Jumonville may have been on a diplomatic mission—not a military one. The French saw it as cold-blooded murder. Washington had fired the first shots of the French and Indian War.

The Fort Necessity Disaster

In retaliation, Washington hastily built Fort Necessity in a muddy meadow. It was barely defensible. On July 3, 1754, French forces surrounded it. After a day of heavy rain and gunfire, Washington was forced to surrender.

Worse still, the surrender document he signed (written in French) accidentally admitted to “assassinating” Jumonville. Washington didn’t speak French and likely didn’t realize the wording—yet it gave the French powerful propaganda.

This would be the only time Washington ever surrendered in his career—but he learned valuable lessons about preparation, logistics, and humility.

A Reputation, Not Ruin

Back in Virginia, rather than disgrace, Washington’s daring earned him fame. He was promoted to commander of all Virginia troops by age 23, a remarkable feat. But friction with British officers—who often looked down on colonial militias—frustrated him deeply.

Still, he pushed on. Washington worked tirelessly to recruit, train, and supply his men, many of whom were poorly equipped and undisciplined. It was a crash course in leadership.

Braddock’s March and the Bloody Ambush

In 1755, Washington joined General Edward Braddock’s campaign to seize the strategic French Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh). Braddock dismissed Native tactics and ignored colonial advice.

It was a fatal mistake.

Outside the fort, French and Native forces ambushed the British in the Battle of the Monongahela. Chaos erupted. Braddock was fatally wounded. Officers fell rapidly.

Washington, though sick with dysentery and not in command, rode fearlessly through the gunfire, rallying troops and carrying out Braddock’s orders.

Two horses were shot out from under him. Four bullets tore through his coat. He was untouched.

Many called it divine protection. Washington’s legend was growing.

Honor Without Command

Despite his heroism, Washington never received a royal commission from the British—something he craved. The class-based British Army looked down on colonial officers.

Disillusioned, he resigned in 1758, shortly after helping in the successful capture of Fort Duquesne. At just 26, Washington had experienced the brutality of war, the arrogance of empires, and the limits of colonial loyalty.

A Warrior Returns Home

By the end of 1758, George Washington returned to Mount Vernon a seasoned veteran. He wasn’t yet a national hero—but he had become something even more important: a man ready to lead, no matter the odds.

He’d faced failure, fought prejudice, and learned strategy under fire. In every way that mattered, the boy had become a commander.

Conclusion: The Fire Before the Flame

Washington’s military years weren’t flawless — they were messy, tragic, and politically frustrating. But in those muddy trenches and dense forests, a young man discovered not just tactics and logistics, but the true nature of power.

He saw empire up close — its arrogance, its bureaucracy, its brutality. And he never forgot.

These lessons would echo 20 years later… when he’d face down that same empire again.